Did you know that two of Martin Luther King Jr.’s children were born in a Catholic hospital in Montgomery, Alabama, because it was one of a few places where Black families in the South were not excluded from quality medical care?

Did you know that the famous marches from Selma to Montgomery in March 1965 to advocate for voter rights culminated on the grounds of a Catholic parish?

Did you know that the late civil rights leader, John Lewis, whose skull was fractured by law enforcement as he crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, was treated by a Catholic health facility which saved his life? And, did you know that when Lewis opened his eyes, the first person he saw was a Catholic priest?

These are some of the stories of the civil rights era that abound among Catholics in central Alabama, but are largely unknown elsewhere. These stories remind us of what the Church has done, and continues to do, in difficult circumstances.

The City of St. Jude welcomes civil rights marchers

Leontyne Pringle remembers marching from Selma nearly 60 years ago with her mother.

When Catholic Extension Society staff visited her, she proudly held up a commemorative map of the groundbreaking 1965 march from Selma to Montgomery.

When asked if it was meaningful to her that the marchers stopped on the grounds of St. Jude Catholic Church, she replied with a smile, “Of course. This is where I went to school.”

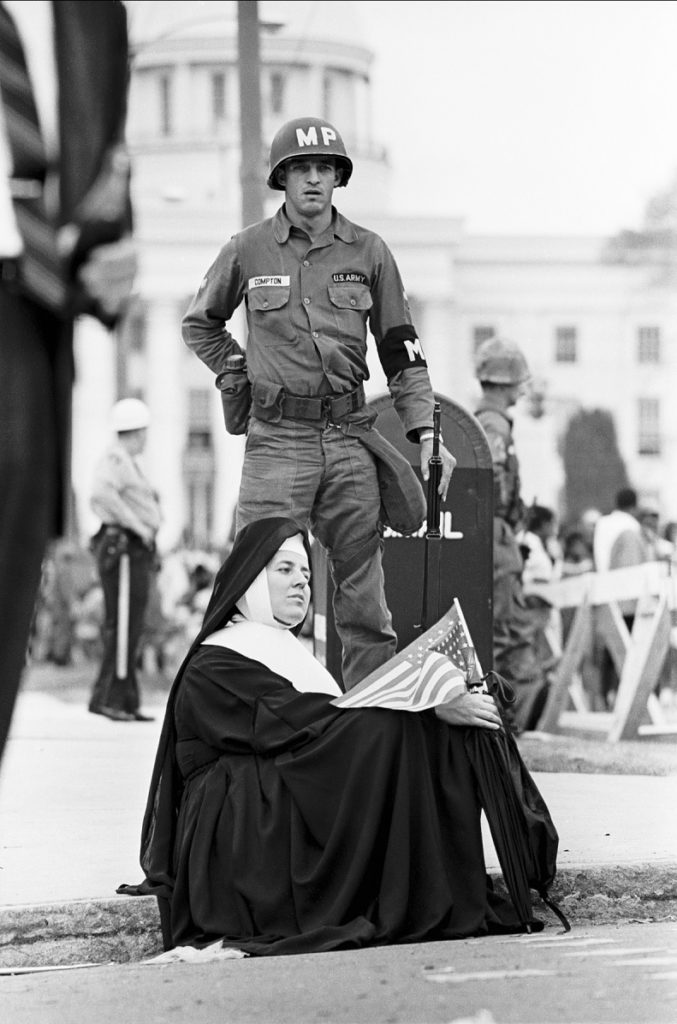

She was alongside many Catholics who traveled from across the country to join the march.

St. Jude Church and School were founded in 1934 to serve Black children and give them education and opportunities. This was during a time when the Alabama state government systematically hindered the economic and academic development of Black people.

The church and school were part of a larger complex called the “City of St. Jude” in Montgomery, which was founded by the late Passionist priest Harold Purcell. It included a racially integrated hospital (the very one where Martin Luther King Jr.’s children were born) and accompanying educational, spiritual, and social services.

The City of St. Jude hosted the “Stars for Freedom” rally the night before the last day of the march from Selma to Montgomery. More than 25,000 people camped out on the grounds, among them celebrities who performed songs to encourage the spirits of the marchers before they set out for the Alabama State Capitol the next day.

Holding the event came with a cost for St. Jude. Apart from the very real death threats from white nationalists, many Catholic donors abandoned them for hosting Martin Luther King Jr., who they regarded as a communist and troublemaker. This setback hobbled St. Jude’s outreach efforts for years.

Nearly 90 years after its founding, they are still doing all that they can to help the vulnerable, despite the fact that Catholics still represent only 2-3% of the population across the state.

Today, the Father Purcell Memorial Exceptional Children’s Center serves as a residence for 45 children with lifelong physical and mental disabilities. The center’s director, Brenda Hicks, a 2020 Lumen Christi Award finalist for Catholic Extension Society, dutifully serves these children and honors their human dignity each day.

She knows she is part of a rich legacy. She was offered this position on the same day she received two other job offers which paid more and did not require her to work third shift. Brenda turned them down. Like the leaders who came before her at the City of St. Jude, she understands the importance of sacrificing for a cause you truly believe in.

Edmundite Missions carve a path of hope

Meanwhile, 50 miles away in Selma, the Edmundite fathers, a religious order of men who arrived 86 years ago as missionaries, also have their share of stories.

Edmundite priest Father Maurice Ouellet befriended Civil Rights leaders John Lewis and Martin Luther King Jr. He helped Lewis after his skull was fractured on the Edmund Pettus Bridge when state troopers attacked marchers on “Bloody Sunday” in 1965.

Father Ouellet was subsequently asked to leave the mission by Church leaders. They feared the priest was getting too close to the civil rights movement and would be killed.

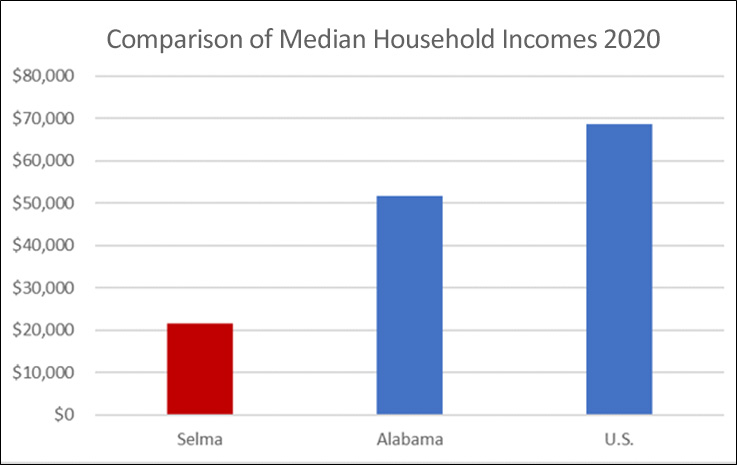

In spite of Ouellet’s painful exile, the Edmundite missionaries stayed in Selma all these years. They continue to provide hope to a community that suffers crushing poverty, poor health, and dismal education attainment levels. More than 45% of children live below poverty in the county where Selma is located, and median household incomes pale in comparison to the rest of the country.

Last month, they served 25,000 meals to the hungry. They continue to offer a health clinic, a desperately needed service in an area where diabetes and poor nutrition are rampant. Their sports and fitness center are a community focal point that promotes healthier lifestyles and keeps kids off the streets.

They offer social enterprises and job training that help people be more employable and economically self-reliant. This includes individuals like William Hope, who learned to read through the Edmundite Missions.

In Selma, where there are still prominent cemetery memorials to KKK leaders, the white Edmundite priests who have died there are buried in the “Black cemetery.” It is a permanent reminder to all that in Heaven, there are no divisions.

This what it looks like when the Catholic Church is firing on all cylinders, and when it lands on the right side of history. And it is what continues to make us believers in the Church’s future potential.

That is why Catholic Extension Society and Holy Family Catholic Community in Inverness are partnering this year with the Edmundites to renovate a dilapidated house in downtown Selma that will house summer interns from Catholic colleges around the country.

The hope is that these college students will not only participate in the life-saving work of the Edmundites, but also gain a deeper understanding of what it means to be Catholic, the courage that it takes, and the beautiful transformation that can happen when we put our faith into practice.

By coming to Selma, these college students will hopefully see that even with its historical baggage, missteps, and past sins, the Catholic Church also has been at its core a force for good in the world.

When our Church remains focused on the mission it was given 2,000 years ago to bring “Good News” to a world that experiences so much darkness and pain, new life is truly possible.

We hope that the unknown stories of yesterday and today about the Church’s heroic work in places like Alabama will be told and re-told so that future generations will come to know the true essence and potential of the Catholic Church in America.