In the fifth century, St. Patrick was forced from his homeland in tears and anguish.

As a teenager, Patrick was captured by pirates in northern Britain, which at the time was part of the Roman Empire. He was shipped outside the boundaries of the empire to Ireland where he was enslaved.

According to his own writings, he followed a voice he heard in a dream that directed him to escape on a ship back to his homeland. Years later, that same voice spoke to him even louder and urged him to return to Ireland. This time, however, he arrived not as a captive but as a missionary.

He became one of the first bishops in history to minister to the “barbarians” (the Celts) who were beyond the reaches of Roman society and law. The Celts were not even considered to be humans by Patrick’s contemporaries. Patrick affirmed their humanity. He is believed to be the first person in human history to openly condemn the evil of slavery.

Patrick’s deep love for the Celtic people, his affirmation of their culture and his concern for their welfare were the hallmarks of his life as he sought to share the Gospel throughout the Emerald Isle.

A patron to many peoples

In the United States, St. Patrick’s legacy lives on in the hearts of our 31.5 million Irish Americans. Moreover, just as St. Patrick extended himself beyond his own country and culture, so too does his following extend beyond the descendants of Ireland, especially among those who have had to tearfully leave their homeland as he once did.

This includes today’s refugees finding safety and new opportunities in America today. Catholic Extension Society is supporting the parishes that are opening their doors to welcome them.

Over 5 million Ukrainians have fled their country since the Russian invasion began in February 2022. About 180,000 are now in the United States. This includes Maryna Pushak and her children, who were welcomed into St. Nicholas Ukrainian Catholic School and Parish in New Jersey.

Roughly 400,000 Congolese have fled their country since the first and second Congo Wars, sometimes called Africa’s World War. Noelle is one of these refugees; she now sings in the Swahili choir at St. Peter Claver Church in Lexington, Kentucky.

In the past 10 years, more than 125,000 Burmese refugees have been admitted to the United States after fleeing tumult in Myanmar. People of the K’Cho tribe escaped poverty and violence in Myanmar. They now attend Holy Spirit Catholic Church in Bowling Green, Kentucky.

Every immigrant has left a land they loved driven not by choices but by brutal necessity. Each immigrant has a heart-rending backstory. These are the modern-day fears and hopes of Ukrainian , Congolese and Burmese families who have fled their homes to find safety and opportunity in the United States. In their parishes, which are supported by Catholic Extension Society, they have found relief and community.

Saying all the names we know for all the lost lands is an exercise in compassion, a widening of heart and soul, a quickening of empathy, and a call to see the face of Christ in all the souls wandering the earth. St. Patrick shares a special bond with all these souls who have lost their land.

St. Patrick’s spirit in America

St. Patrick’s ability to prevail in the face of suffering, to affirm the humanity of others and to share the Gospel with people of other cultures are revered attributes that continue to resonate with people across the globe. These are among several reasons why he continues to be celebrated and loved all these centuries later.

As evidence of his enduring popularity, Catholic Extension Society has records dating back to 1905 that indicate that we have helped build or repair hundreds of churches named after the beloved saint. These churches are located across the country, from Montana to Puerto Rico. Each one is a unique chapter in the story of St. Patrick’s legacy in America.

The following three communities each possess their own special connection to St. Patrick. Each shows how the spirit of St. Patrick remains alive and well today throughout our country.

St. Patrick in Puerto Rico

Loíza, Puerto Rico, is home to one of the oldest Catholic parishes under the American flag. Founded in 1645, St. Patrick is its patron.

The town has a predominantly Black Caribbean population that descended from enslaved people brought from Africa. It is believed that the slave ships stopped in Loíza to dispose of the slaves who were on the brink of death after the grueling journey across the Atlantic Ocean. Those who survived eventually settled in Loíza. How did this Black Caribbean community descended from former slaves come to adopt the Irish saint as its patron?

The community had experienced multiple devastating yuca famines and was searching for a powerful intercessor. Yuca is a root vegetable and major food staple in the Caribbean, much like the potato was in Ireland. The people turned to St. Patrick for help. When the yuca famine ended, which they attributed to the power of St. Patrick, they re-dedicated their church and added St. Patrick’s name, becoming Holy Spirit and St. Patrick Church.

The parish celebrates St. Patrick’s Day with intensity and joy. However, there is no Irish dancing on March 17. To honor its patron, the community dances “La Bomba,” a traditional drumming and dance celebration with origins in Africa.

In the 1980s, the parish’s pastor asked Samuel Lind, a local artist, to depict St. Patrick as Black. The painting is proudly displayed in the parish.

St. Patrick among Montana miners

One of the areas with the highest percentages of Irish descendants in the United States is Silver Bow County in western Montana. The county is more than 25 percent Irish. The region is part of the Diocese of Helena, where Catholic Extension Society has been supporting parishes for more than a century.

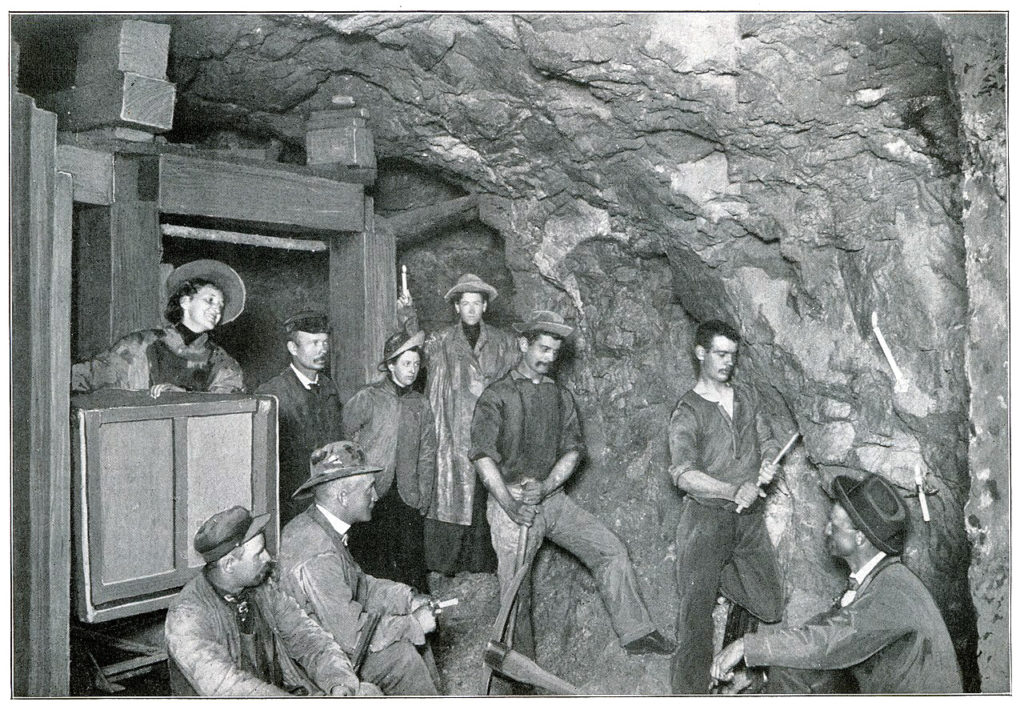

St. Patrick’s Catholic Church in Butte, the country’s main city, was built in 1881. For decades, many Irish immigrants came to Butte to work in the silver and copper mines following Ireland’s Great Potato Famine. As these sons and daughters of Ireland left their homeland, they, like St. Patrick, brought their faith with them.

The town welcomed the Irish workers at a time when “Irish Need Not Apply” signs were wide-spread across many major cities. However, the working and living conditions in the Butte mining camps were unfair and deadly. Determined to no longer live under suppression as they had in Ireland at the hands of the British, the workers fought for decades to secure their economic interests by forming labor unions.

How many Irish workers walked into the dangerous mines over those years with St. Patrick’s famous breastplate prayer on their lips?

Christ with me, Christ before me, Christ behind me, Christ in me, Christ beneath me, Christ above me, Christ on my right, Christ on my left.

St. Patrick’s in Butte and the other Catholic churches in Montana were centers of community strength for these generations of people struggling to survive and make a living in a new land.

Today, the spirit of St. Patrick remains strong in Butte. Each year, more than 30,000 people gather to celebrate their beloved saint and Irish heritage on March 17.

St. Patrick on the plains of Texas

Just off the old Route 66 highway that cuts through the Texas panhandle sits a little town called Shamrock in the Diocese of Amarillo. The name of the town is not a fluke.

Kathleen Cross, a lifelong parishioner at St. Patrick’s church, said that her grandfather was born on a boat coming over from Ireland in 1876. He and other Irish settlers bought land in Shamrock and built dugouts (rustic lodges made of earth), where their families would live until they could build permanent homes.

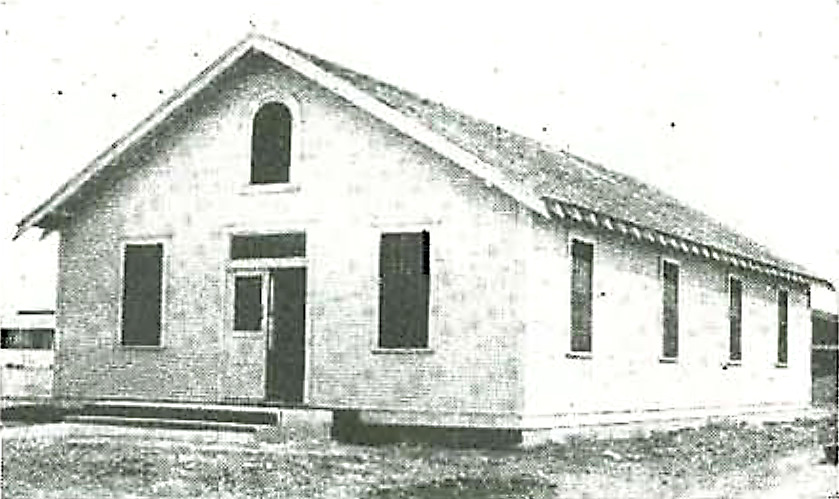

Cross said her grandfather contacted the diocese right away to bring a priest to the settlement. A priest would arrive by train, celebrate Mass in someone’s home, and leave the next day. In 1929, Catholic Extension Society helped build the church.

Cross has heard the story all through her life; the dedication was on St. Patrick’s Day, and 17 children were confirmed. Catholic Extension Society also helped build a new church for the parish in 1966 as the community continued to grow.

Today, the parish shares a pastor with Our Mother of Mercy, located 25 miles south, in Wellington. It was also built in 1929—yet another church that Catholic Extension Society helped build and has supported over the years.

These Catholic communities today have a mix of families of European, Hispanic and Filipino descent. Each brings its rich traditions and celebrations to the parish. “We’re a very diverse community,” Cross said. The blend of cultures offers many occasions to celebrate.

St. Patrick’s Day is of course, a joyous event in Shamrock. Students in religious education classes build a float to take down Main Street every year. The priest dons a St. Patrick’s Day hat and greets festival attendees.

Likewise, the feast of Our Lady of Guadalupe is a much-celebrated event, as more Hispanic families have been welcomed into the parish, which now offers bilingual Mass. Filipino families celebrate Simbang Gabi, an Advent tradition. “It’s a wonderful celebration. We have a Christmas party and exchange gifts and games,” parishioner Monica Kidd said. She continued,

It’s a small, friendly community. I’ve been tied there my whole life.”

The spirit of St. Patrick, which sought to affirm the Gospel’s relevance for all cultures and peoples, is very much present in these rural Texas faith communities, whose diverse parishioners recognize that they share so much in common in faith.

The parish in Shamrock is a loving symbol of the Celtic knots that decorate churches in Ireland, the United States and the cover of our latest magazine. The endless unbroken knots, with no clear beginning or end, signify our unity amid God’s eternity. The spirit within each human soul, regardless of background or ethnicity, is one with God the Father, Son, and the Holy Spirit.

“We’re all connected,” Kidd said.

This story first appeared in the Spring 2023 edition of Extension magazine. Read about a fourth community supported by Catholic Extension Society that shares multiple special connections to St. Patrick: Two legendary “Patrick’s” in El Paso.