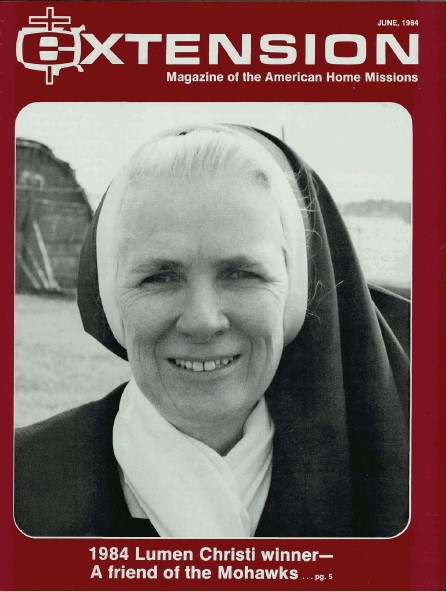

This is a retelling of a 1984 Extension Magazine article highlighting that year’s Lumen Christi Award recipient, Sister Mary Christine Taylor. Global Sisters Report featured Sister Taylor in a November 2020 Q & A.

In 1969, the Mohawk of upstate New York made international news when they blockaded the reservation bridge that crosses the St. Lawrence River between the United States and Canada.

The Mohawks were protesting tariffs charged to them by U.S. and Canadian customs in violation of a 200-year-old treaty prohibiting such taxes. Their St. Regis Reservation occupies both American and Canadian soil. The protest restored the Native American rights to duty-free crossings. But the activism scared many non-Native people living near the 24,000-acre reservation.

“People would drive long distances to avoid the reservation because they didn’t understand what was going on,” remembers Sister Mary Christine Taylor, SSJ.

The conflict did not frighten Sister away, however. Reading past the headlines, she sensed that the problems of the Mohawks were caused by many years of misunderstanding and discrimination by non-Natives. These misgivings had led the Mohawks to feel isolated and angry—emotions Sister has worked to unwind over the past 12 years.

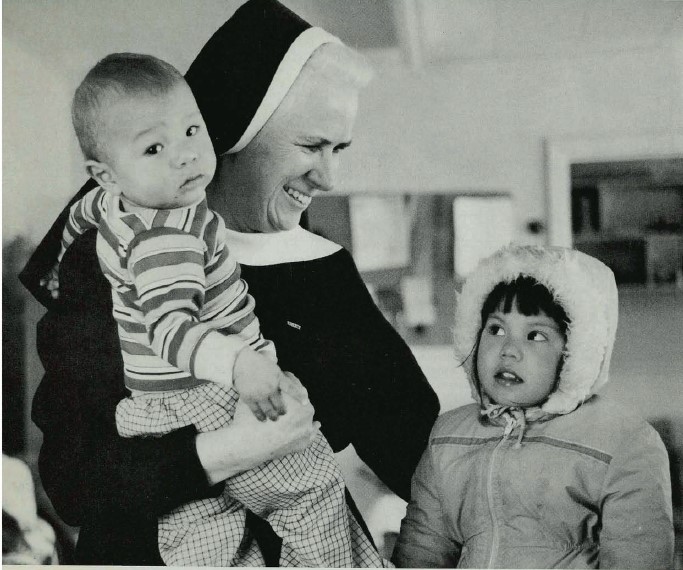

“The stereotype most people have of the Mohawks is unjust because they are a very talented and faithful people,” said Sister Taylor, who was honored with Extension’s 1984 Lumen Christi Award for her dedicated work to restore the faith of the Mohawks in the Church and society.

“Once you are their friend, the Mohawks will do anything for you, even die for you. That is why it is such a crime that white men have broken promises such as the bridge tariff.”

Born and raised an hour’s drive from St. Regis in Ogdensburg, N.Y., Sister Taylor admits she did not fully understand the Mohawk’s plight before coming to the reservation. At the heart of the Native’s protest is a lack of self-respect, she now believes.

“Many of the Native Americans can tell you of discrimination in school where they were beaten if they talked in their own Mohawk language. The children were made to feel deprived and inferior because their teachers did not understand why they wanted to maintain the Mohawk heritage. So many Mohawks dropped out of school at very early ages.”

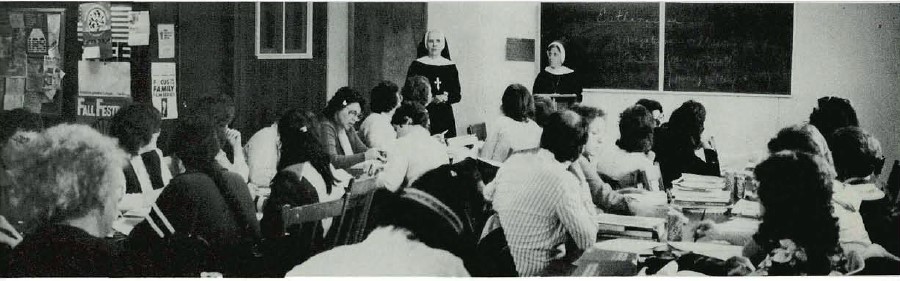

To help the Mohawks re-establish themselves, Sister Taylor, then academic dean of Mater Dei Catholic College in Ogdensburg, brought the first college extension classes to a Native American reservation in 1972.

For 10 years, she commuted 60 miles a day between the college and the reservation. By day she counselled the Ogdensburg students, and by night the Native Americans. After the last class at 10 p.m., she raced back to Ogdensburg to care for her aging mother who died two years ago.

Christ never said He would cure our poverty because the poor will always be with us. But He has come to help us elevate our lives and realize that we can be materially poor but spiritually rich with His grace and His life.”

Sister Mary Christine Taylor

Sister’s passion to help the Native Americans came in part from the example set by her late mother. The youngest in an Irish family of nine children, she was deeply inspired by her mother’s own sacrifices for her family.

“My father died during the Depression. I remember my mother rising early in the morning to tend the garden, and staying up at night to mend our clothes.”

Sister especially recalls one Christmas Day when her mother put the family’s last dollar in the church collection basket. “One of my brothers was frightened because that was all we had to eat with. But my mother told us, ‘The Lord provides. You can never lose by giving to the Church.'”

When the family returned, they found a basket of food on the porch. “Right on top was a little doll for me. I have never forgotten that day.”

The “grace of God” led her to join the Sisters of St. Joseph of Watertown, N.Y., where she started a teaching career. In 1963, after having taught in both elementary and secondary schools, she became chairman of the history Mater Dei, a small liberal arts college staffed by St. Joseph Sisters. She soon became Mater Dei’s academic dean but avoided the ivory tower which might have kept her away from those who truly needed her help.

As a religious sister, I see my presence here as saying that God does love the Native people because He cares enough to send me to bring His son to those truly in need.”

Sister Mary Christine Taylor

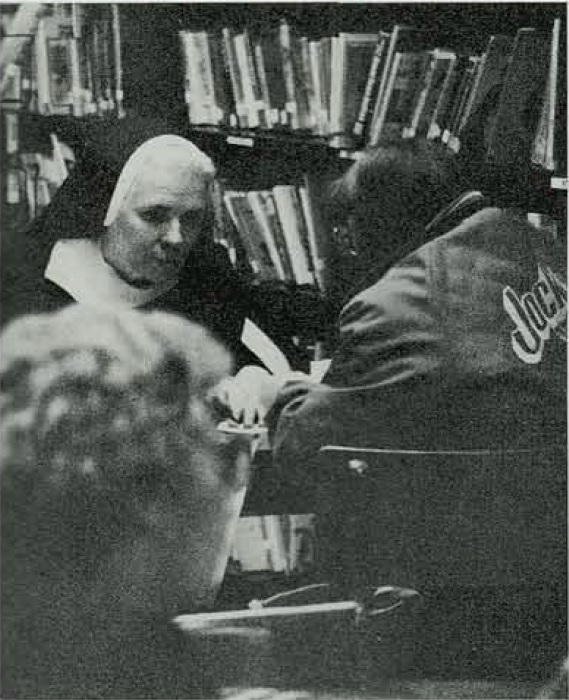

Working on the reservation, Sister now devotes all her time to the Mohawks. She helps set up courses, find tutors and financial aid, and counsel students when they are discouraged. Her attention to each student’s needs makes the difference, according to Margaret Jacobs, one of her graduates who is now library director. “Sister has a way of showing everyone how truly special they are.”

Today, most community services on the reservation are run by Mohawk graduates of Sister Taylor’s program. They include alcohol rehabilitation counsellors, school teachers, nutritionists, librarians and nurses. The reservation’s first medical student is starting her final year of residency.

“In 12 years, they have gone from dropouts to college graduates,” Sister happily reports.

Things are looking up all over the reservation. The Mohawk run their own school, newspaper and museum. Mohawk language is now taught in public schools. Elders instruct the children in Mohawk arts that include everything from basket-weaving to song and dance.

Poverty is still visible, however. The number of ancient log homes and mobile trailers far surpass modern bungalows.

Most men leave their families for months to travel around the county seeking ironwork. At the height of the recession, unemployment among the Native Americans hit 75 percent. But hope remains because of Sister’s work.

“Christ never said He would cure our poverty because the poor will always be with us. But He has come to help us elevate our lives and realize that we can be materially poor but spiritually rich with His grace and His life,” said Sister Taylor who, in her white summer habit, could be mistaken for an angel.

She almost floats across the rolling wooded reserve on her various errands of mercy for the Mohawk poor, the elderly, alcoholics and struggling young people. Her veil streaming out from white locks of hair, the piercing look of her eyes, and a disarming smile all convey her angelic appearance.

Sister, however, prefers another title—messenger of Christ. “What I enjoy most is bringing Jesus Christ to the people, not only by taking Holy Communion to the elderly but in counselling and listening to the adults’ problems and in trying to help them realize that nobody has the answers to all the problems of family life, unemployment or alcoholism.”

Her message—learned during her childhood—is that there is hope in struggle, joy in sacrifice for others. It is a message she lives and has transmitted to many of the 7,000 Mohawks.

“As a religious sister, I see my presence here as saying that God does love the Mohawk people because He cares enough to send me to bring His son to those truly in need,” she said.

Although she recognizes education as the principal means by which Native Americans may improve their lives, her outreach has gone much further. She helps the Mohawks with religious needs—preparing them for the sacraments and teaching Catholic truths. When the reservation mission lost its previous pastor, she kept catechism classes going.

When the elderly needed assistance with food and necessities, she helped start a nutrition center which serves hot meals to almost 60 persons. She helped begin a halfway house for alcoholics.

Many Mohawks have obtained skills, higher education, employment, and a sense of achievement because of her.”

Most Reverend Stanislaus Brzana, then-Bishop of Ogdensburg

Sister also does the little things that win hearts—a hug for a nursing home resident or a new Easter suit for a crippled shut-in.

“How many college deans do you know who stop and spend as much time with senior citizens as with their students?” asked Father Thomas Egan, SJ, pastor of St. Regis Mission. “She knows everyone on the reservation and has helped mission work enormously by opening doors to the many Native people she has befriended over the years.”

Although most of the Mohawks have been baptized Catholic, many are no longer practicing because of the turmoil on the reservation. Sister has been quietly restoring confidence in those who fear the Church.

“We have been teaching that you can be a good participant in your language and culture and be a good Catholic,” said Sister, who knows some Mohawk language. “We have Native hymns and prayers in our Mass and even the early Jesuits were very good about translating prayers into Mohawk.” Beatification of the Mohawk maiden, Kateri Tekakwitha, also has encouraged the Natives.

Working into the night with no salary stipends, Sister lives on sack lunches made by the Mohawk senior citizens and occasional donations from those who admire her dedication.

At 53, despite two operations which robbed “some of my energy,” she still races to her work, rising with her community of sisters at 5:30 a.m. and working until late. She intends to continue working on the reservation “as long as God wills it.” The Light of Christ she has shared on the reservation will continue to illuminate the Mohawk’s lives for many generations.

“Many Mohawks have obtained skills, higher education, employment, and a sense of achievement because of her,” said Most Reverend Stanislaus Brzana, Bishop of Ogdensburg, who nominated Sister for Extension’s Lumen Christi Award.

“Countless others have been given a concrete hope that they, too, can succeed in making better lives because their friends and neighbors have done so with the help of Sister Christine, the Church, and new programs and services that work. This new attitude of hope is bringing peace to the reservation.”

Catholic Extension Society supports sisters just like Sister Mary Christine Taylor. You can help their ministries, building up vibrant and transformative Catholic faith communities in the poorest regions of America.