Last month I made a visit to the U.S. Virgin Islands still in the midst of recovery from hurricanes Irma and Maria. The visit was strangely disquieting: I was in a place of great natural beauty, hoping to serve people in their rebuilding efforts, and yet I found that the experience highlighted the profound historic and social challenges that are unique to this place.

Bishop Herbert Bevard describes his diocese as “a very poor part of the richest country in the world.” In a press conference hosted by Catholic Extension Society last November, he pointed to the double difficulty of people first having lived through two Category 5 hurricanes, and second having to respond to the loss of income resulting from the absence of tourism—the industry that touches nearly everyone on the islands and which is their economic base.

In my visit to Frederiksted on the island of St. Croix, I saw something of the challenges facing the U.S. Virgin Islands. There was a massive cruise ship docked at the pier. This is a normal and frequent occurrence there, but during my visit, the ship was the temporary home to many relief workers trying to rebuild basic infrastructure. Just a couple of blocks away stands St. Patrick Church, a historic building badly damaged by the storms. Another two blocks away I visited a former convent that serves as a retreat center. The bishop dreams of turning it into a homeless shelter, but the hurricanes left it badly damaged.

Hurricanes are a regular feature of life in the islands. Many years earlier, in the wake of a hurricane that had devastated St. Croix, a 17-year-old young man described “the prodigious glare of almost perpetual lightning, the crash of the falling houses, and the ear-piercing shrieks of the distressed.” The year was 1772, and the young man was Alexander Hamilton. While in St. Croix, he worked for a merchant and dealt directly with slaves arriving from West Africa, helping prepare them for sale. At the time, there were 22,000 African slaves living on the island and only 2,000 members of the European merchant class.

Today the population of the U.S. Virgin Islands is still to a great extent descended from slaves. The 2010 census shows a population that is nearly 80 percent black or African American and only 15 percent white—a ratio not very different from Hamilton’s time. A third of the 105,000 residents live below the poverty line, with per capita annual income of just above $13,000, around 35 percent below that of Mississippi, the poorest state in the continental U.S.

For centuries, there have been two sides to the reality of these islands: one, that of a wealthy island paradise; the other, that of a place where local residents eke out a living, often in poverty. Hurricanes Irma and Maria tore down some of the distinctions between these two realities, in the middle of which stand many of the Church’s ministries.

I visited Sts. Joachim and Ann Church in Barrenspot, St. Croix, where a chapel built in 1823 stands next to the old sugar plantation’s slave quarters. I also saw Sts. Peter and Paul Cathedral, just down the road from the very marketplace where slaves were bought and sold on the island of St. Thomas.

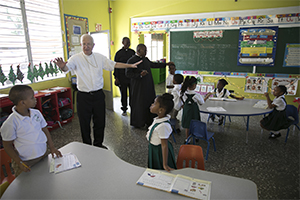

I visited schools, too, such as St. Joseph High School on St. Croix, where the seniors were all dressed up for picture day, and Sts. Peter and Paul School on St. Thomas, which had just gotten a fresh paint job from Catholic teen volunteers a few months earlier. Catholic Extension Society has been privileged to fund these and other ministries over many years, sending over $82,000 last year alone.

It was at Sts. Peter and Paul Cathedral, next to the school, that we celebrated the Mass of the Feast of the Immaculate Conception. The students sang a beautiful closing Marian hymn, the refrain of which is written on the wall below the choir loft. Its French recalls the Belgian Redemptorists who ministered to the poor French-speaking residents for generations.

The hymn is an expression of transcendent hope, to see the Mother of God in heaven:

Au ciel, au ciel, au ciel,

j’irai la voir un jour.

In heaven, in heaven,

I will see her there one day.

Many residents of the Virgin Islands have carried heavy burdens over generations, compounded by the regularity of devastating storms such as those that hit a few months ago. The hymn is a reminder that one day they will be able to lay their burdens down and enter into the embrace of a loving Mother in heaven.

In the meantime, though, it is up to us to help ease their burdens.

Dr. Tim Muldoon is Catholic Extension Society’s Director of Mission Education.