This month marks the 60th anniversary of the three historic marches for civil rights in Selma, Alabama. In March of 1965, thousands of people from across the country descended on the small town to support the rights and dignity of Black Americans through nonviolent protest—despite the very real danger of violence upon themselves.

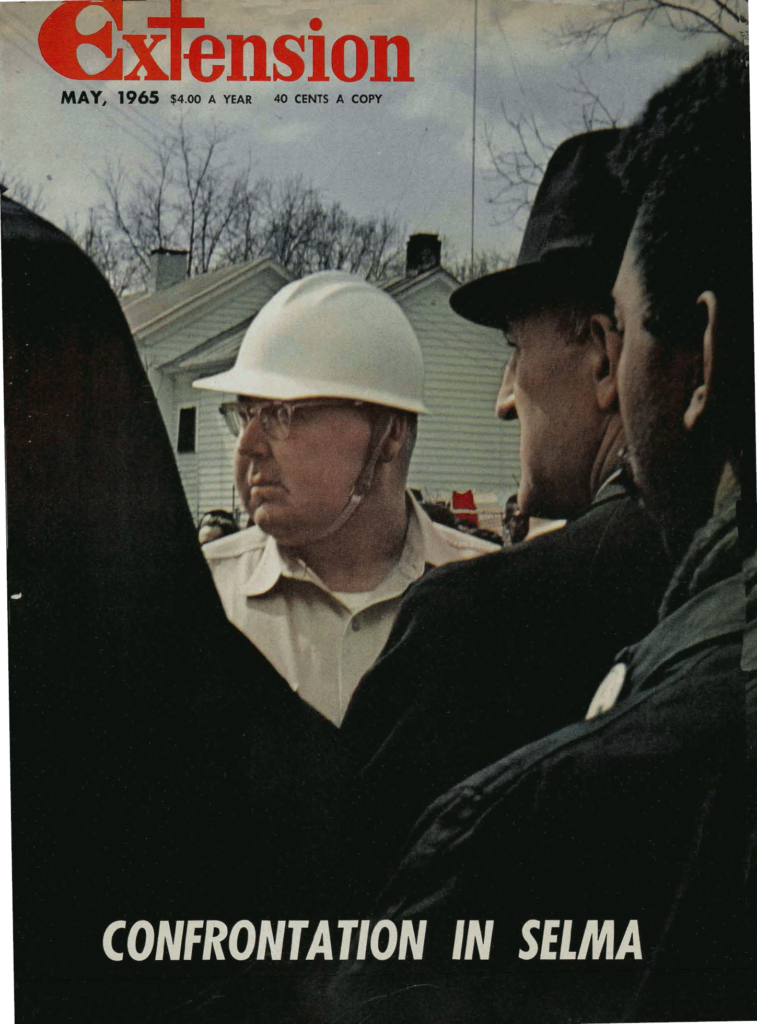

In remembrance of this turning point in history, we look back at how our publication, Extension magazine, covered the events, and the lessons they derived from this important moment in history.

Catholic Extension Society joined the Catholic Church’s marchers by sending a staff member, Jerome Ernst, who participated in a march. The impassioned article he wrote on his experience was printed in Extension Magazine following the events.

He is pictured below taking part in the demonstrations:

It became the cover story of our May 1965 issue. Ernst photographed a priest, a nun, and another protester in front of an Alabama trooper blocking the marchers.

An introduction to the article in the magazine noted that not all Catholics and Christians were behind the movement:

“To most of the closed minds, the Selma incident was strictly and exclusively political; the Church should keep out of it. Obviously, they have ignored or not even heard of Pope John’s social encyclicals, Christianity and Social Progress (Mater et Magistra) and Peace on Earth (Pacem in Terris), which not only condemned racial discrimination but also urged men and women to become involved in social and political affairs.”

During this fraught moment in our nation’s history, Ernst reflected on how the Church must respond:

Selma was a call for a moral revolution of Christian witness and love in the hearts and minds of Americans.”

Despite naysayers, the Catholic Church was heavily involved in the movement.

Many Catholic leaders and institutions stepped up to the cause and traveled immediately to Selma to join the march, including priests, nuns and laypeople from across the country.

Additionally, the “Stars for Freedom” rally—the celebratory last night of the final Selma to Montgomery march where tens of thousands gathered—culminated on the grounds of St. Jude Catholic Church.

Ernst recently wrote to Catholic Extension Society about the experience.

“I heard about the beating at the bridge and immediately headed South, scared stiff, alone with nowhere to stay as I found my way through the line of troopers,” he said.

He also shared that civil rights leader Andrew Young, then deputy to Martin Luther King, Jr., told him that if it wasn’t for the National Catholic Conference for Interracial Justice, Selma would not have happened.

Ernst faced a very real threat against his life, as did his thousands of fellow protestors.

The first march took place on March 7, 1965, with the aim to support voting rights and confront the governor after an Alabama state trooper shot and killed a protester, Jimmie Lee Jackson, during a recent nonviolent demonstration.

On their way to the capital, 600 unarmed protesters were met with violence on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma.

They were brutally beaten by state troopers, leaving 17 marchers hospitalized—including future Congressman John Lewis.

The widely televised attack shocked the nation. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. called on religious leaders from all over the nation to join a march two days later to support “our peaceful, nonviolent march for freedom.”

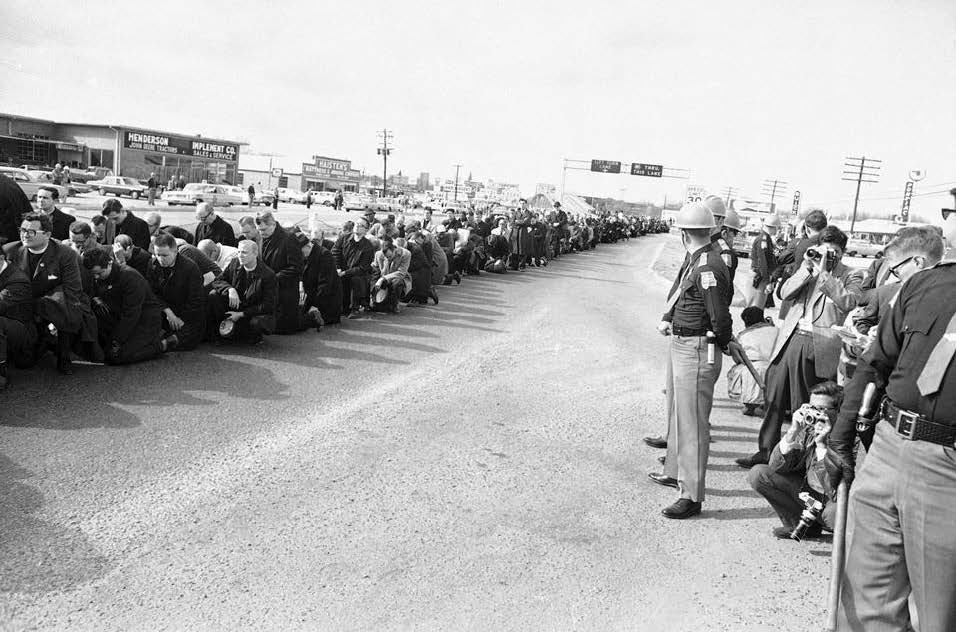

Hundreds of clergy members came to Selma to show their support.

On March 9, Dr. King led about 2,000 marchers back to the bridge, but they did not cross it in order to avoid another confrontation.

That night, Reverend James Reeb, a white Unitarian minister from Massachusetts, was beaten with clubs by the Ku Klux Klan. He died from his injuries two days later.

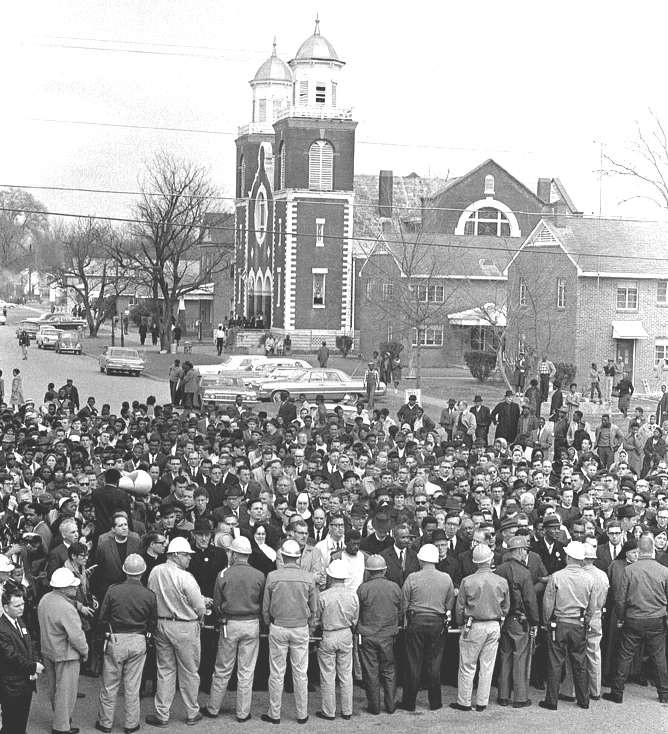

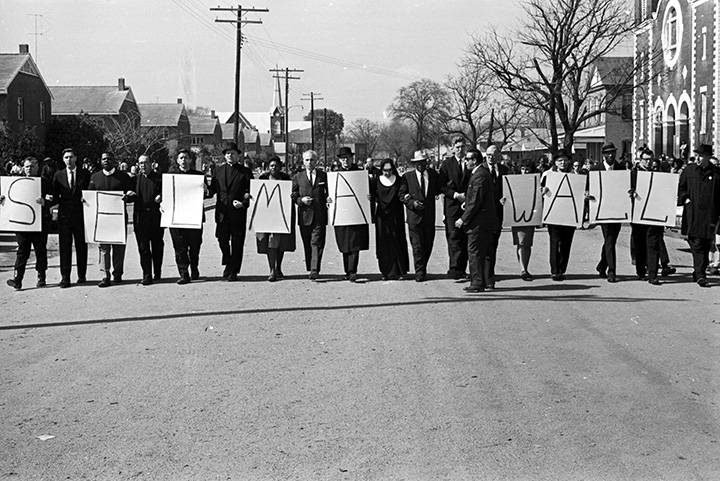

In the days following, religious leaders and Selma students gathered at Brown Chapel AME (African Methodist Episcopal) Church to protest, sing and pray against the “Selma Wall,” a line of troopers and police officers created to prevent further marching.

The third march was held from March 21 to 25. On the final day, 25,000 marchers, including many Catholics, gathered before the Alabama state capitol building in Montgomery.

That night, Viola Liuzzo, a mother of five from Michigan, was murdered by the KKK while she was driving marchers back to their lodgings.

Catholic Extension Society still has a personal, ongoing connection to this movement in American history by supporting Catholic communities involved in the marches. In fact, this past October, a group of priests traveled with us to Selma on one of our pastor immersion trips.

They had the opportunity to meet people who marched 60 years ago and learn about the incredible work of the Church to serve the poor of this community today.

The priests walked in the footsteps of the marchers. They crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge, where marchers were confronted by police on Bloody Sunday.

“My trip with Catholic Extension provided an opportunity to see the remarkable work that the Church engages in every day. This work so often goes hidden and unnoticed,” said Fr. Robert P. Boxie, III (middle, below), Catholic Chaplain at Sister Thea Bowman Catholic Student Center at Howard University in Washington, D.C. “I am proud that our Church continues to uplift in concrete ways the dignity of all human beings, especially in communities and populations that are marginalized, neglected, and forgotten. In the missions in Alabama, I learned about the Church’s historic role in the fight for civil rights; although imperfect, the Church was still present.”

Father Michael Trail (far left, below), pastor of St. Thomas the Apostle in Hyde Park in Chicago, was one of the trip participants. “To be able to see the work of Catholic Extension come alive in Mississippi and Alabama was deeply, deeply moving to me,” he said.

Below is the 1965 article from Extension magazine. It wrestles with the idea of how the Church was being called to be a witness of hope and defender of people’s dignity in a time when the nation and people of faith were deeply divided about the direction of the American society.

May we reflect on their words, doubts and struggles, as we discern how the Church is called to be a leavening force and herald of Good News in today’s world.

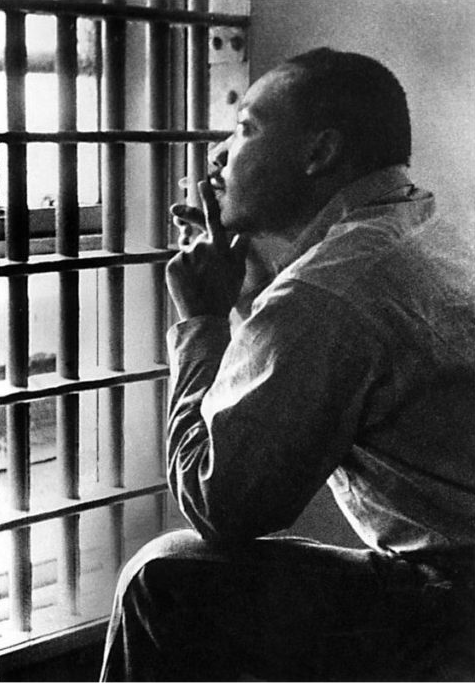

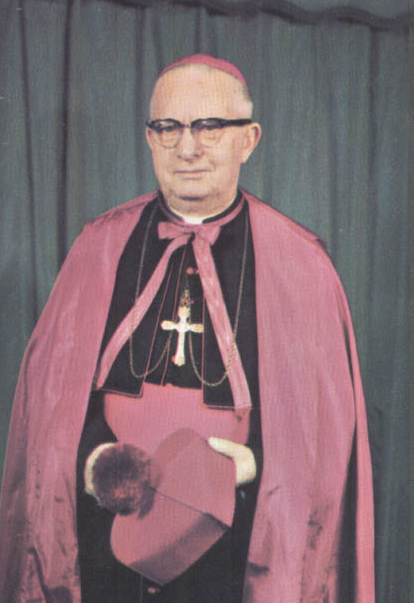

The article begins with the image below, captioned:

“We shall overcome: The face of Rev. Donald Schilling, California Presbyterian pastor, registers the moral indignation of the nation over Selma. Participation of priests, nuns, ministers and rabbis in unprecedented numbers signaled a turning point in the commitment of churches to racial justice.”

The article then provides quotes from Martin Luther King Jr. and then-Archbishop Robert E. Lucey of San Antonio:

Letter from a Birmingham Jail: Challenge to the Church

Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

April, 1963

“I hope the church as a whole will meet the challenge of this decisive hour. But even if the church does not come to aid of justice, I have no despair about the future. …We will reach the goal of freedom in Birmingham and all over the nation, because that goal of America is freedom. Abused and scorned though we may be our destiny is tied up with America’s destiny.

“Before the pilgrims landed at Plymouth we were here. Before the pen of Jefferson etched across the pages of history the mighty words of the Declaration of Independence, we were here. For more than two centuries our forebears labored in this country without wages; they made cotton king; they built the homes of their masters while suffering gross injustice and shameful humiliation—and yet out of a bottomless vitality they continued to thrive and develop. If the inexpressible cruelties of slavery could not stop us, the opposition we now face will surely fail.

“We will win our freedom because the sacred heritage of our nation and the eternal will of God are embodied in our echoing demands.”

The Church’s answer

Archbishop Robert E. Lucey of San Antonio

March, 1965

“Fortunately, the voice of religion has been heard in Selma. Protestant ministers, Jewish rabbis and Catholic priests have gone there from many parts of the nation to give witness to the faith that is in them and to play a vital role in brotherhood.

“And Catholic sisters, God bless them, marched down the streets of Selma giving testimony to the charity of Christ in need and in truth. The conscience of America has revolted against the atrocities of Selma and the brutal denial of freedom.“

Some Catholics will maintain that the participation of priests and nuns is improper, Archbishop Lucey said.

These Catholics should remember, he wrote, that Christ “demonstrated vigorously one day” when He drove the moneychangers out of the temple.

The Significance of Selma

By Jerome Ernst

“We must make America a place where man is willing to deal with his problems. Only when problems are raised can men deal with them.”

So said Rev. James Bevel, Alabama civil rights leader, as we began one of the many Selma marches that culminated in the historic March of Montgomery.

Demonstration had been given as to the best way of protecting our heads from the troopers’ clubs. We were instructed that if arrested we were to cooperate with the dignity benefiting our cause; names and phone numbers of the next of kin and friends were taken so that those jailed would have outside contacts.

No one was to touch a trooper, we were told. We were simply to present ourselves as a confrontation; we were to expose our bodies to possible violence like that at Selma bridge; we were to give physical witness to the cause of human rights. We were scared.

A moral revolution of nonviolence was taking place around me. I believed in such a revolution. Up to now I didn’t have to do anything about it that involved danger for me, even though I had participated in other interracial-activity. Now I was to present my head to the troopers as a Christian witness in the cause of social justice.

Selma showed me I was not simply involved in a civil rights movement; I was not merely promoting integration. I was involved in a new way of life. I was invited to consider a new Christian posture. The posture of Jimmy Lee Jackson who was shot down by an Alabama trooper, because he stood up for his rights. John Lewis, Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee leader, who was clubbed down at Selma bridge. The posture of Father Maurice Ouellet, Selma pastor, who sheltered demonstrators, though he was himself forbidden to participate in the marches. The posture of Mrs. Viola Liuzzo, mother of five who came from Detroit to participate in the march and was slain by a sniper while driving some marchers back to Selma.

Selma raised problems. Selma asked questions. These questions will be asked again and again until the right answers are given. Selma asked—what is man? Not what is black man, nor what is white man. But what is man? Martin Luther King’s marchers raised this question by their personal, nonviolent confrontation before the Selma and Alabama power structure.

The troopers tried violence. They hid behind a show of force and brutality as an escape from the problems. The power structure tried to avoid the questions and cloud the issue. But they could not escape the nonviolent witness of hundreds of priests, nuns, ministers, rabbis and laymen, Negro and white, who stood up for justice in Selma.

“Too long have we been converting to Jesus with the tactics of Pilate,” said Rev. Bevel. Passive resistance was basic to the Christian message, he said. Problems must be pointed out in the spirit of love.

But many still refuse to have the message.

“We didn’t have any problems until troublemakers came along,” a Selma resident declared.

Another said:

“The white folks were happy; the [racial slur] were happy before these outside agitators came into town. Now it will never be the same; the [racial slur] will expect to be equal to us and they just ain’t not as intelligent as us white folk.”

He was right. It will never be the same again. Selma was a turning point.

Selma showed that truth and love will work its torturous way into American society if people are willing to suffer and to stand up for it. Selma’s greatest sermons were preached at the Selma Wall and at Selma bridge.

Selma has settled the question of voting rights for Negroes once and for all. But it was more than that. Selma was a call for a moral revolution of Christian witness and love in the hearts and minds of Americans.

“We are not interested in the color of people’s skin, but in the color of peoples’ faith.” So said Rev. C. T. Vivian, a leader in the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. This is the point of Selma and the civil rights movement—the color of people’s faith.

A priest put it this way: “I come to apologize for our apathy, our insensibility in doing so little in the past; your struggle should long ago have been our struggle. The next time we of the Roman Catholic community will take Rev. Reeb’s place. We will in the future do together what we should long ago have done together.”

The speaker was Msgr. Daniel Cantwell, chaplain for Chicago’s Catholic Interracial Council, who himself had long been involved in the fight for human rights.

Religious leaders of all major denominations took to the streets in Selma. They supported a nationwide nonviolent resistance movement armed with the weapons of love and forgiveness. Even the singing at the Selma Wall echoed this theme:

Selma needs you, Lord; come by here.

Sheriff Clark needs you, Lord; come by here.

Children are suffering, Lord; come by here.

We love the troopers, Lord; come by here.

It wasn’t planned that way, but Selma became a high point in ecumenism, too.

When a Maryknoll nun preaches in the African Methodist Episcopal Church before Baptists, Episcopalians, Unitarians, and Catholic priests and laymen—that’s ecumenism.

When Catholic priests clap hands and shout out Negro spirituals—that’s ecumenism.

When a New Jersey priest donates $50 to the cause in the name of his parishioners—that’s ecumenism.

Jimmy Lee Jackson and Rev. James Reeb and Mrs. Viola Liuzzo were truly martyrs in the cause of human rights. The nation owes them this: that they will not have died in vain.

The civil rights marchers are confident that America will rise to the challenge of democracy. “We will win our freedom,” Martin Luther King, Jr., says, “because the sacred, heritage of our nation and the eternal will of God are embodied in our echoing demands.”

The Negro is inspiring a moral revolution, a new social consciousness in America. The survival of democracy depends upon the extent to which we are willing to commit ourselves to this revolution.

President Johnson underscored it: “The real hero of the struggle is the American Negro. . .. Their cause must be our cause too.”

In Selma people stood up for freedom, for justice and the world took note. If this Christian witness can work in Selma, it can work in Chicago’s south side; it can work in South Africa. And this is the significance of Selma.

Catholic Extension Society continues to have a close relationship with Selma and other communities in the Deep South where the battle for civil rights carried on for so many years.

We work in solidarity with Catholic leaders and parishioners such as Leontyne Pringle, who participated in the final Selma to Montgomery march as a little girl.

Additionally we recently supported the repair of a building that is housing volunteers for the Edmundite Missions in Selma.

The area is economically depressed, but the Edmunites are uplifting the community by providing free meals and education, healthy youth programs and aiding seniors.

The bravery, sacrifice and faith of the Selma marchers inspires our mission today as we continue our 120-year-long mission to work in solidarity with the Catholic leaders advocating for justice and dignity for everyone. Click here to support our mission today!