On July 16, 1945, Eugenia Vega saw the brightest, most terrifying flash of light over the New Mexican desert sky where she lived. As a resident of Carrizozo, she was less than 40 miles away from the Trinity site, the location chosen by members of the top-secret Manhattan Project to test the world’s first nuclear bomb.

The same terrifying light would appear in the world a couple months later, in Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan.

The film “Oppenheimer,” nominated for 13 Academy Awards, including best picture, shows the Trinity test from the perspective of the scientists who built the bomb. Strapped with goggles and sheltering in structures built to protect them from the blast, they eagerly and nervously await the results—not knowing if the bomb will fail to detonate or set off a chain reaction that would consume the entirety of the Earth.

Anyone living within 200 miles could see the unearthly light. They had no idea it was coming, and no idea what it was.

The testing site was supposedly chosen because the region was “uninhabited.”

But, for the people of Carrizozo (with a population of more than 1,400 in 1945, and 972 residents today), this area is home. “The sun had just come up,” said Eugenia Vega. “It was like 6 o’clock in the morning. And then this white flash. Just everybody, everybody panicked.”

She and her parents ran into St. Rita Catholic Church, located just behind their home. It filled up with their panicked neighbors—just about everyone from the small ranching town that could fit.

Everybody thought the world was ending. It was such a big flash.”

“They were going to the church, filling the church, saying the world was ending. People were crying, running around. I was only 7,” she said.

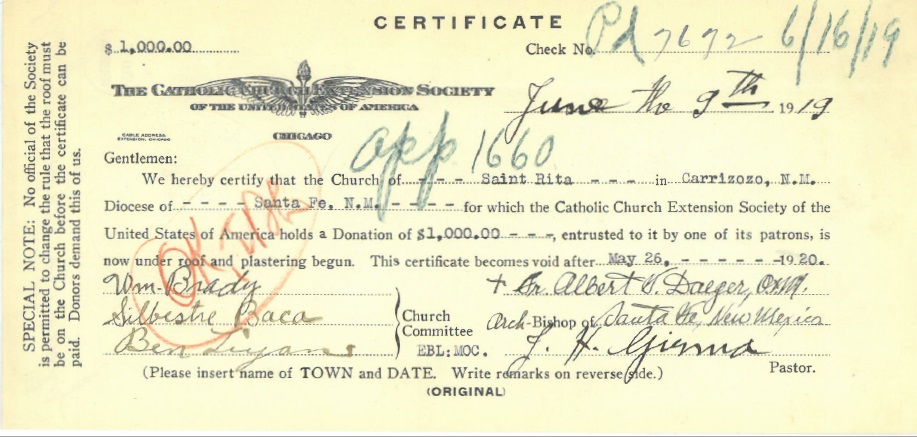

Catholic Extension Society has been with the St. Rita community in Carrizozo since 1919, when we first helped build the original church, as indicated on this archived record.

That Extension-built church (one of more than 13,000 across the nation) became a place of convening and consolation on that day in 1945 when a 38,000-foot tall mushroom cloud cast its shadow on the humble town.

In some ways, that shadow never fully dissipated.

Ongoing impact of the bomb

The long-term consequences of the first nuclear bomb within the town of Carrizozo were devastating.

Several parishioners—from left to right below, Polly Chavez, Mac Chavez, Faustino Gallegos, Eugenia Vega, and Nicholas Vega—shared how the event has affected their lives.

The decades that have followed the Trinity test in Carrizozo have been times of great struggle as this small community grappled with this catastrophic event. The government did not reveal the whole truth for many years.

Today, every single person in Carrizozo knows someone who has been diagnosed or died of cancer. They attribute this to the environmental impact of the test.

Faustino Gallegos is a parishioner at St. Rita. He was born three months after the Trinity Test. His little sister, born in 1947, only lived for three days.

Annie Serna is the parish director. She was born in 1951. Her sister, born a few years after the bomb went off, died at 6 months old. That was just the beginning.

“I have two sisters that have passed away from cancer. I had cancer. My brother now has cancer. And I have a nephew that has cancer,” she said.

The townspeople knew something was wrong. The bomb’s cloud eventually fell down from the sky, casting a white ash over everything.

Horses and cattle, many raised on ranches even closer to the blast, had their fur burned off.

“They wouldn’t let the children out because they didn’t know what it was,” Eugenia said. “Nothing was green anymore.”

Nothing grew for a long time.”

But for years, they didn’t know about radiation, or contamination in the water and soil. Although they were suspicious of how the land was impacted, they also depended on it for survival. They continued to eat meat from the cattle. They continued to drink from their own wells. There was no other water to drink.

The town’s new pastor, Father Thadayoose Lazar, serves St. Rita as well as Sacred Heart Mission, located 20 miles away, and St. Theresa of the Little Flower in Corona, located 47 miles away. He knows the trials that the parishioners have faced as he presides over the funerals of elders.

“It’s a sad story,” he said. “There was no announcement to leave town.”

The residents have never received assistance or compensation from the government for the damaging, lifelong effects of the test.

Rather, faith and friendship have kept this community together.

Mac Chavez, a lifelong resident and parishioner, said,

The good thing about Carrizozo is that we all know each other.”

His wife, Polly Chavez, loves that everybody meets up at the post office every day.

“All our parents were hardworking people,” Eugenia said. “You just keep going to work.”

“We’re all friends, we’re all neighbors,” she said. “We’re just average people in a small town. We know about each other, care about each other.”

They shared a selfie together outside St. Rita’s Church:

Faith was their protection in the face of an atomic bomb

Faith was the only defensive measure that the people of Carrizozo could turn to when they believed the world was ending.

This is exactly what Eugenia’s grandparents did. The moment the bomb went off, her grandfather saw the light of the explosion when he was washing his face outside, as he did at that time every morning. When he ran inside to his wife, she instinctively started to pray the rosary.

A running theme in “Oppheimer” is the lead scientist’s eventual awareness and guilt of the real “chain reaction” of nuclear armament. What has been set off cannot be stopped.

The residents of Carrizozo have known this truth since the day the bomb went off. They knew from that moment that their futures had changed forever.

Indeed, the future of all of humanity has been altered since that fateful day, because the threat of nuclear war persists in our world.

This past week, Pope Francis, marked the International Day for Disarmament and Non-Proliferation Awareness, with remarks in that called disarmament a “moral obligation.” Likewise in 2022, he said “a world free of nuclear weapons is necessary and possible.”

Meanwhile, in Carrizozo, life moves forward, with the faith of the people kindling their hope for a brighter future.

Two years ago, Catholic Extension Society helped the parish with significant repairs to the church, parish hall and rectory, so that this faith community could continue to come together to praise the God who created our beautiful Earth which has been scarred by human sin. St. Rita Church is also a place where people support one another as they strive to build a home centered on God’s love amid a world where there is so much capacity for violence and destruction.

Catholic Extension Society will continue to work in solidarity with the faith community of Carrizozo and the people of this hallowed land who share a harrowing history.

Catholic Extension Society works in solidarity with people to build up vibrant and transformative Catholic faith communities among the poor in the poorest regions of America. Please support our work!