When Pope Francis addressed the U.S. Congress on September 24, 2015, he pointed to the witness of Martin Luther King, suggesting that a great nation “fosters a culture which enables people to ‘dream’ of full rights for all their brothers and sisters.” As we remember the 50th anniversary of his assassination, it is important to recall the hard work of social change that helped bend our nation in the direction of greater justice. The integration of Catholic parishes and schools in Mississippi provides an important window into the moral struggles that existed inside the Church’s own institutions, a struggle that can provide important lessons for us today as our society continues to confront difficult matters of race, justice, and equality in America.

In the decade between 1955 and 1965, Mississippi was a hotbed of racial unrest, and Catholic schools and parishes were not immune. It was a period sandwiched between two racially motivated murders which drew national attention: the murder of the 14-year-old boy Emmett Till in 1955, and the Freedom Summer (or “Mississippi burning”) murders of three young civil rights activists in 1964. It was a place of dramatic racial tension both within the Church and in the wider society. Today, as the nation’s attention focuses on college basketball, it is worth remembering too that 1963 was the year that the all-white Mississippi State University team had to sneak out of the state to play in the “game of change” against an integrated Loyola University team which ultimately won the NCAA title.

In 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court had struck down as unconstitutional any state laws that segregated students in public schools. Yet Brown v. Board of Education applied only to public schools, and so Catholic schools in Mississippi remained segregated into the early 1960s. Many parishes, too, were places where white majorities made blacks feel unwelcome or, in some cases, unsafe. Groups of whites threatened black Catholics attending Mass at Saint Joseph in Port Gibson; Sacred Heart in Hattiesburg; Saint Joseph in Greenville; and many others.

Yet there were many people who earnestly desired that white churches be more welcoming to blacks and who worked toward integration as a gospel mandate.

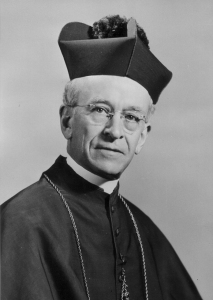

One key figure was Bishop Richard Oliver Gerow. He had been nurturing hopes for desegregation of his parishes and schools for years, keeping meticulous files of racial incidents. A realist, he understood that episcopal fiat could not undo generations of racial prejudice, and so worked slowly to develop collaborators.

In 1954 an incident at a church in Waveland gave rise to extended correspondence between Bishop Gerow, Father Michael Costello, the pastor, and Father Robert E. Pung, S.V.D., the rector of Saint Augustine Seminary, the first black seminary in the United States. During the previous year, Father Costello had arranged with Father Pung that he would send a priest to celebrate Mass in Waveland each Sunday. In early 1954, Father Pung sent Father Carlos Lewis, S.V.D., a black native of Panama. Some weeks later, Father Pung received a phone call from a parishioner threatening injury to any other black priest who might be sent. Pung subsequently composed a strongly worded letter to the man. He writes, “The Catholic Church clearly teaches (following Christ himself) that all members are one, that there is no distinction of color within her fold.” He cites the first letter of John: “If anyone says, I love God, and hates his brother, he is a liar. For how can he who does not love his brother, whom he sees, love God, whom he does not see?” (4:20).

He closes with a defiant tone, telling the man that no one in a Church with a history of martyrdom, and thousands of members of the clergy now suffering in Communist prisons, will be scared by his threats. He writes,

And what did the priest come to your parish to do: just one thing – to celebrate Mass and bring Christ down upon your parish altar and to feed the flock of Christ with his Sacred Body. And that the majority of the parishioners looked upon the priest celebrating Holy Mass as a priest of God and not whether he was colored or white is evident from the fact that last Sunday over three Communion Rails of people received Holy Communion from his anointed hands.

He assures the man that these same priests would be praying for him.

Bishop Gerow kept an extensive file including this and many other racial incidents, mindful that he was an actor in an important chapter in both Catholic and American history. The file contains many similar stories of black Catholics being harassed by white parishioners over the years. Taken together, these tragic stories, as well as the Bishop’s reflections on them in his diary, show him trying to navigate this period of escalating racial tension while remaining focused on the moral imperative of creating pastoral structures that serve all God’s children. In one entry from November 1957, he shares the advice he gave to a group of Catholic men who were distressed at the ill treatment of black parishioners. He wrote:

we are facing a situation in which we as a small minority are up against a frantic and unreasonable attitude of a greater majority of the community. If we attempt to force matters we are liable to do injury not only to ourselves but also to those whom we would wish to do help, namely, the Negroes. Imprudent action on our part might cause them very serious even physical harm. Therefore, we must be very careful in what we do.

His position on desegregation was a delicate one, which attempted to balance a complex array of factors and forces:

- First, there were the pastoral needs of black Catholics in the region, some of whom had to travel to celebrate the sacraments and who sometimes faced verbal or physical threats.

- Second, there were the established parishes comprised mostly of whites, themselves a minority in a region that was dominated by Protestants.

- Third, there were men in both state and local government, not to mention law enforcement, who were sometimes hostile even to white Catholics, and so the presence of blacks in Catholic congregations was a further potential danger.

- Fourth, there were a growing number of organizations supporting the cause of integration: those in organizations like the NAACP and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, as well as Catholic organizations like the National Catholic Welfare Conference and the National Catholic Conference for Interracial Justice.

Bishop Gerow was not alone in his concern to find the right way to integrate Catholic institutions, but he faced ambivalence both within and outside his diocese. In 1958, the National Catholic Welfare Conference—a precursor to today’s United States Conference of Catholic Bishops—issued a statement, “Discrimination and Christian Conscience.”

Some historians argue that the bishops’ statement was slow to be issued and not forceful enough in its stance toward desegregation. Nonetheless, it provides valuable insight into the Catholic Church’s growing moral convictions on the problem of segregation.

Addressing the question of enforced segregation, the document asks, “Can enforced segregation be reconciled with the Christian view of our fellow man? In our judgment it cannot….” It offers two reasons: first, segregation makes one group inferior to another; and second, it leads to the denial of basic human rights of blacks. It closes with an exhortation to act now to “seize the mantle of leadership from the agitator and the racist,” but stops short of recommending specific actions.

Two years after the bishops’ statement, Mathew Ahmann, the founder and executive director of the National Catholic Conference for Interracial Justice (NCCIJ), and later one of the organizers of the March on Washington, wrote a piece in Commonweal (12/2/1960), “Catholics and Race,” placing the bishops’ statement in the larger context of the race question in the United States. He points to 45 Catholic interracial groups in the United States dedicated to desegregation and to addressing housing discrimination. In the South, he reports, the previous year showed that only 6 percent of African American students were in integrated schools. In Mississippi, moreover, there were none.

He highlights the fact that just prior to and after Brown v. Board, Catholics had taken the lead in integration, citing the examples such as Archbishop Joseph Ritter of Saint Louis, who had begun desegregating Catholic schools in 1947 (threatening excommunication to any who protested). Ahmann goes on to lament that “Catholic activity in the interracial movement in the South has in recent years all but come to a halt.” Nor was the situation much better in the North, where discriminatory housing practices impacted many black migrants from the South.

It was Ahmann’s NCCIJ colleague Henry Cabirac, Jr. who began to force the hand of Bishop Gerow, when Cabirac called for integration of schools at meetings in Mississippi City in the middle of 1963. Responding to Cabirac’s advocacy that black families apply for admission to white Catholic schools, Gerow wrote in his diary of July 1 the following:

My point is this: School integration is going to come in the course of time, but at present we are not ready for it. I feel that the first step is to create a better relationship between the two races, and to accomplish this I have written to the pastors of the Diocese that they have several sermons on the race question in their church and have offered to give them sermon outlines to guide them, the purpose of this being to create a realization that we are all children of God and that the colored have certain God-given rights many of which they have been deprived of in years past.

Only two days after this entry, on July 3, the bishop wrote that he had received letters from two black families requesting admission of their children to schools “which we have considered white.” He laments being in an embarrassing position, feeling that “a bit more preparation of our whites is prudent.”

No doubt the bishop was sensing great tension in the air. Only two weeks earlier, the field secretary for the NAACP, Medgar Evers, had been assassinated, and once again the nation’s attention was on Mississippi. The immediate aftermath of the assassination saw Gerow in a political role to which he was naturally averse. In his diary, he wrote “Up to this time, I have refrained from making any public statements in the newspaper. At times I would feel that maybe it would do good, and at other times, I felt that our work might be better accomplished by working quietly with our committee [of religious leaders].”

He had been active in drawing together white ministers in the various churches in Jackson for some time, and in fact had arranged for a meeting that included black ministers only five weeks earlier. The groups had hoped that their combined voices might thaw the icy relationship between blacks and the Jackson Chamber of Commerce. But after the assassination, the bishop felt compelled to make a public statement which he shared with the press.

The statement, published June 14, two days after Evers’ death, begins with an assurance of prayer for his wife and children. He had reached out personally to Evers’ widow Myrlie, commenting in his diary that their children were students at the Catholic school in Jackson. He points to the shared guilt for his death among all people, in light of the racial situation, but also points to the failure of responsible leadership. Like the 1958 NCWC document on race, Gerow’s statement recalls the Declaration of Independence and its recognition of the self-evident truth of equality before God. He prays that leaders will take “some positive steps” toward solving the crisis, though does not identify what those might be.

The Evers assassination had pushed Gerow to a more public position on the race question, and at the time that meant taking a strong moral stand. Yet with Cabirac’s address, Gerow found himself facing a very practical question: namely, what to do about the integration of schools which, he was certain, had to happen someday. In his letter to pastors of June 19, 1963, he stresses the need for them to speak to their congregants about race, impressing upon them “that we are not asking for the granting of concessions to the Negro but for a recognition of his rights.”

The opportunity to act decisively happened one year later, July 2, 1964, when President Lyndon B. Johnson signed into law the Civil Rights Act. Bishop Gerow issued a statement to the press the next day.

Each of us, bearing in mind Christ’s law of love, can establish his own personal motive of reaction to the Bill and thus turn this time into an occasion of spiritual growth. The prophets of strife and distress need not be right.

On August 6, the bishop published a letter to be read in all churches the subsequent Sunday (August 9), indicating that “qualified Catholic children” would be admitted to the first grade without respect to race. He called on all Catholics to “a true Christian spirit by their acceptance of and cooperation in the implementation of this policy.” In a letter to his chancellor, Gerow describes this move as “more in accord with Christian principle than of segregation.” The following year, he desegregated all the grades in Catholic schools.

Senator Hubert Humphrey, the floor manager of the Civil Rights bill in the U.S. Senate, went on record saying that churches were “the most important force at work” in the movement. Today, Humphrey’s observation offers a challenge to us as we continue to confront racism. The church can serve not only as a moral voice on society’s toughest issues, but also can a staging ground within her own institutional structures for the transformation that we hope to bring about in society.

In recent months, we have also seen tragic examples of racially motivated hate crimes. Later this year, the U.S. Bishops plan to release their first pastoral letter on racism in nearly forty years. Mindful of the gifts that people of all races bring to the community of faith, and of the need to work towards a just social order, USCCB President Cardinal Daniel DiNardo said at the launching of the racism task force last August, “The vile chants of violence against African Americans and other people of color, the Jewish people, immigrants, and others offend our faith, but unite our resolve. Let us not allow the forces of hate to deny the intrinsic dignity of every human person.”

Also, later this year is the Fifth Encuentro, a gathering of Hispanics which highlights the graces in this largest-growing segment of the US Catholic population. This historic convening is taking place as questions of immigration dominate our political discourse, especially the fate of the young, so-called “Dreamers,” who have lived in this country most of their lives and yet have no place in it. Indeed we face many important moral questions, that the Church must struggle with today which will have many ramifications for the future.

For over a hundred years, Catholic Extension Society has been serving dioceses with large populations of the poor, the marginalized, and people of color, and have sent millions of dollars to ensure that they have infrastructure and well-trained Church leaders that will form them for positive social change.

Our dream is that these leaders will, in the words of Pope Francis, “awaken what is deepest and truest” in the life of the people, and ultimately be the catalyst of transformation in their communities.

The examples of Bishop Gerow provide important lessons for how that might happen. Despite the complex political and historical factors regarding the question of desegregation in Catholic institutions, Gerow ultimately listened to his inner moral convictions to pursue the course of action that he believed to be the truly Christian thing to do.

On this 50th anniversary of Martin Luther King’s assassination, we are mindful of all those Christians who have gone before us in the struggle for a more peaceful and just society, so that we may be inspired by their example to confront and struggle with the pressing questions of our day. Bishop Gerow’s extensive efforts to chronicle the important period of his episcopacy remind us that we too live in the midst of a history that others will remember and judge in the light of God’s call to live justly.

Thanks to Mary Woodward, chancellor of the diocese of Jackson, for her assistance with the Bishop Gerow archive, from which the historical material in this article is drawn.

Tim Muldoon is the author of many books on Catholic theology and spirituality, and serves as the Director of Mission Education for Catholic Extension Society.